They take you up on Townhill at night to see the furnaces in the pit of the town blazing scarlet, and the parallel crossing lines of lamps…If it is always a city of dreadful day, it is for the moment at that distance a city of wondrous night.

Edward Thomas, ‘Swansea Village’

I: The Bombing

In 1914, when The English Review published Edward Thomas’ essay ‘Swansea Village’, the town was at the peak of its industrial wealth and prestige, a position that would be temporarily damaged by the First World War (a war Thomas would not survive: he was killed in action in Arras on Easter Monday, 1917). Thomas’ portrait was debated by the Swansea Council Library Committee, with angry objections raised to descriptions of the town as “a dirty witch” and “compared to Cardiff…a slattern” (1, although in response to Thomas’ judgement that “many of its dark-haired and pale skinned women are beautiful,” Mr Moy Evans objected, “he is all wrong about the women”). In fact, as at least one person present noticed, Thomas had successfully conveyed the paradoxical qualities of the town. It was left to Mr Crocker of the Committee to explain, with bracing common sense: “I beg your pardon, he says the town is witchingly attractive…nobody ever said that Dickens ruined London when he painted Bill Sykes.” As Thomas recognised, and Dylan Thomas would later immortalise, Swansea is a town of insoluble contradictions, inspiring mixed emotions that amount to something more than mere hometown ambivalence. Part of this has always been due to despair at the scars of industry and urban disrepair, a despair equally matched by delight in the natural beauty of the bay. Although the comparison was never as exact as later claimed, in 1826 Walter Savage Landor did write: “The Gulf of Salerno, I hear, is much finer than Naples; but give me Swansea for scenery and climate. I prefer good apples to bad peaches” (2). There also remains, dating from its failure to become a famous Georgian seaside resort, a sense of unfulfilled potential that persists despite a rich industrial history and city status. It is probably impossible to write well about Swansea without running the risk of offending somebody from there, although most will recognise this conflict of feeling.

This conflict was intensified by the destruction of the town during the Second World War. Swansea was one of many major Blitz targets in Britain and while the bombing did not equal the tonnage dropped on cities like London, Liverpool or Birmingham, the concentration of the attack was as ferocious. Swansea and Gower had been subject to random, individual bombing since June 1940, with the first significant air raids taking place in September and the following January, but it was the devastating three night raid of the 19th-21st February 1941 that was subsequently remembered as the Swansea Blitz. In concentration and effect, this attack resembled Coventry: Swansea’s commercial centre was almost completely destroyed, causing a profound historical, physical and psychological rupture for the town.

This was the result of a change of strategy by the Luftwaffe. In early 1941, Luftflotte 3 began to target the west coast seaports that served Allied shipping routes in the Atlantic, switching to night raids following heavy losses during previous day time bombing campaigns. Like Coventry, whose fate was sealed by unusually bright November moonlight, the success of the Swansea Blitz was the result of atmospheric luck: the nights of the raids were cloudless, with moonlight bouncing back off a fresh layer of February snow, creating conditions of exceptional visibility. The first night set the pattern: pathfinders lit up the town with parachute flares and incendiary bombs, illuminating key targets for the main bomber force that saturated the town with thousands of incendiaries and high explosives. By the third night, huge fires consumed the centre. The water mains had been severed by the previous bombing; hoses stretched from the North and South Docks in a desperate attempt to stop the fires, but were continuously destroyed by explosions (3). Neath, Port Talbot and Llanelli dispatched rescue parties which struggled to get in due to bomb-cratered roads and the debris of collapsed buildings. The glow in the night sky caused by the fires could be seen from the far end of the Gower Peninsula.

After three nights of bombing seven thousand people had been made homeless and the commercial district almost entirely razed. Social cohesion remained and the town was not abandoned, but the Evening Post quoted an eyewitness who succinctly articulated the emotional impact of the raids, stating simply: “Swansea is dead”. The scale of the destruction was an existential event: the industrial infrastructure had survived, but the ruthless immolation of the old town defined the postwar development and identity of the city.

II: The Rest of the World

What made this identity, and what happened to it? The key to these questions lies in the relationship between the town and everything outside of it: both the international contacts which made Swansea a key industrial port, but also its relation to Welsh nationalism and the construction of a ‘Welsh’ identity that took form in the Twentieth Century.

Swansea was established by Norse raiders who first settled at the mouth of the River Tawe during the tenth century and gave the town its name. Following the Norman Conquest, Henry I transferred the commute of Gwyr to his trusted vassal Henry de Newburgh, the Earl of Warwick, who, recognising the natural advantages of the Tawe, made Swansea his headquarters and built a castle. Exercising the rights of a Marcher Lord, Warwick founded a borough originally populated by non-Welsh settlers who established a successful agricultural market centre and port community of merchants, fishermen, mariners and boatbuilders. For Swansea, modern history began with the Acts of Union, which proved a mixed blessing: the town was absorbed into the new county of Glamorgan, losing its caput status to Cardiff but also tying it into an administrative system facing East towards English markets. From this point, because of the Union settlement and its commercial and political benefits, Swansea thrived. During the Tudor period, the town was able to exploit government policies to capitalise on existing trading contacts and geographical advantages. As a result of rapid population growth that stimulated the economies of all existing Welsh towns after 1540, Swansea’s identity as market destination, international port and centre for crafts and services was enhanced. This had been achieved by immigration, settlement and external investments; through integration into the wider Tudor economy, and exploitation of the international trading links that could be accommodated by the Tawe harbour. It is worth noting that the Act of Union effectively gave the Welsh equal legal status to the English, thereby encouraging local migration from the Welsh-speaking rural communities into English-speaking towns. Like other South Wales towns, therefore, the administration and culture of the Swansea elite remained English, but Welsh-speaking settlers started to become part of the linguistic and social mix.

Swansea, therefore, was more than ready for the Industrial Revolution. As Glanmore Williams wrote: “[t]he foundations of the future industrial greatness of Swansea and its environs were already being laid in Tudor and Stuart times and the way being prepared” (4) for the era of coal and metal. In fact, the town was an early exporter of coal: shallow outcrops had been mined in the Swansea valley and North Gower from the Elizabethan era, finding ready markets in Somerset, Devon, Cornwall, the South Coast of England and France. By the early eighteenth century Swansea was a busy coal port with hungry export custom in France and Ireland and a population swollen by the large influx of workers from the surrounding countryside and Ireland. The next stage in the town’s evolution was once again driven by outsiders: English entrepreneurs with the necessary wealth and expertise established a thriving metal-smelting industry, importing copper and zinc ores from Bristol, Cornwall and London and strengthening links between Swansea and the West Country. By the end of the nineteenth century, the growth of tinplate manufacturing fed a hungry American market, opening long-lasting trade links and migration routes to the new continent.

The construction of a great system of docks accelerated the political and cultural development of the town, linking it into a global network of import and export trading partners. Copper, zinc and iron ore imports landed from South America, Cuba, Australia, and later South Africa, Algeria, Chile, Venezuela, California, Italy, Spain, Norway and Sweden. The American tinplate market dwindled following the 1890 McKinley Tariff, but new customers were found in South America, China, Japan and Europe. Coal and patent fuel exports reached France, Italy, Germany, Spain, Sweden, Brazil, Algeria and America. As industry grew and wealth accumulated, the middle classes moved away from the social and ecological furnace by the Tawe: as Victorian suburbs spread west, to the uplands and higher, the townscape became more refined, with the building of Georgian-style villas like Belgrave Gardens and elegant, tree-lined terraces like Walter Road. In the gardens and parks, such as Cwmdonkin, the air was clear, the view back over the town decorated with the red glare of the furnace and the winking rhythm of Mumbles Lighthouse. These years before the First World War, the precise moment captured in Edward Thomas’ essay, represented a peak in Swansea’s industrial history. This was emphatically not a provincial story: in 1913, with a record six million tons of global exports, Swansea was a town with much more than parochial interests.

In fact, the First World War led to a slump in Swansea’s productivity: the copper and tin plate works ossified before the war and lost out to external competitors after it; hostilities meant the temporary loss of important markets in Germany, Austria and Belgium; while conscription gutted the mines of their workforce, thereby limiting exports from the South Wales coalfield. However, Swansea was revitalized during the interwar period by two strokes of fortune: the decision of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company to open a refinery at Llandarcy, and the sale of the entire port to the Great Western Railway Company which linked the town into the world’s largest dock system. By the Second World War, Swansea was importing crude oil from the Persian Gulf, with 10,000 ton tankers discharging cargoes from Abadan, Haifa and Tripoli (5), while exporting refined petroleum, coal, iron and steel products to Europe, America, Canada and Argentina. This was the town Dylan Thomas grew up in, watching “the dock-bound ships or the ships steaming away into wonder and India, magic and China, countries bright with oranges and loud with lions” (6), a place to be reckoned with and closely connected to the rest of the world. The port expanded and modernised, and was there to be converted to wartime purposes when required: after 1939, the docks took war production orders, handled weapons and the transit of troop reinforcements. The sheer scale of Swansea’s productivity and prestige made it a target for the Luftwaffe in 1941, but the irony is that through strategic confusion and apart from one early, isolated attack on the King’s Dock in July 1940, the Germans left the port facilities intact, while destroying the rest of the town. With the centre in flames and water mains severed, it was the hose pipes stretching out from the docks that came closest to saving Swansea’s old heart.

III: ‘The Broken Sea’

The burning of an age.

Vernon Watkins composed a powerful epitaph for this erased town in his long poem ‘The Broken Sea’. This may not be obvious at first, because the poem is a very broad canvas in which Swansea plays one part. A cycle of twenty shorter poems, formally separate yet thematically entwined, it is dedicated and partially addressed to Watkins’ Godchild, “Danielle Dufau-Labeyrie, born in Paris, May 1940”: this birth, and its date, is the foundation for a sprawling meditation on destruction and creation, darkness and light, their cycles and interdependence, obscurely rendered through esoteric Christian symbolism and neo-Romantic imagery. It is, in its way, potent, poignant, even epic, and places the Swansea Blitz within a wider international and even cosmic context: “the burning of an age.”

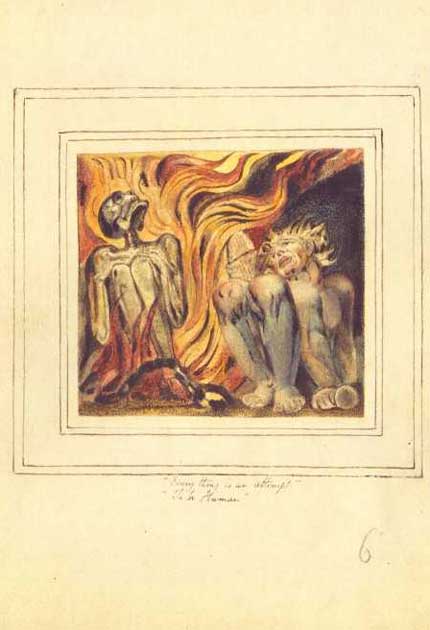

The poem opens with an invocation of “the visions of Blake,” the first in a series of literary reference points that provide their own specific, personal associations (a habit that Watkins indulged throughout his work, dismissed by William Wootten as “paying minor homage to major talents,” 6): Dante, the Books of Job and Kings (“Elijah was fed by ravens”), Hans Christian Anderson, Hölderlin and Kierkegaard. This referential texture provides clues to the coordinates of a rarefied and singular cosmology that seeks, in the grand sweep of the poem, to make sense of the birth of a child within the context of the invasion of France, the bombing of Paris and the destruction of Swansea. The network of symbols created by Blake is crucial to this poem and its imaginative root in dualism and antithesis, the opposition of darkness and light with all of their spiritual associations and implications. The second poem of the cycle is set in Paris after the opening of the Nazi offensive in May 1940, with the city making preparations for the bombing raid that would finally come in June. Plunged into darkness (“‘Put out the lamps! Put out the lamps!’”) but for “a long shaft of moonlight” the City of Light is shut down in anticipation of night attack: people walk in darkness, “moving in ghostly ritual”, “the shroud descending” over Notre-Dame and the Sorbonne, while “singular lives” are “found in the deeper dark…the restive weariness and writhing cramps/of sleepers underground.” Light is a threat in this atmosphere, and people live in shadows or hide in darkness; Paris, crepuscular, cowering, scared of the future (like the new born child, “bursting with terrors to be”) presages the blackouts and Underground station shelters of the London Blitz and the destruction of Swansea: “Perishing in a moment, in a night,/A wave running over the Earth”. These dark shadows both contrast and are entwined in the imagery of light that shrouds the newborn child in her cradle, portrayed by Watkins as a vivid transfiguration:

A cradle in darkness, white.

It must be heavenly. Light

Must stream from it, that white sheet

A pavilion of wonder…

But also a violent conflagration:

...meteors; thunderbolts hurled

From clouds; coil upon coil of spiral flame. (8)

The child becomes a symbol of the future, of hope and light, but in the shadow of a portent: a future of fire, violence and fear that Paris will face within a month and Swansea within a year. The date that Watkins names (“I remember the tenth of May”) also contains this duality: it is the date that Hitler unleashed his blitzkrieg on the West and, though Watkins does not allude to this, the day that Churchill became Prime Minister.

The ninth poem of the cycle is Watkins’ epitaph for Swansea. It is also the section that caves into rage and despair, listing landmarks that have been obliterated, leaving memories suspended in a void. It is the most vivid section of the poem, and possibly why it was the only part anthologised by Kenneth Allott in his 1951 Penguin Book of Contemporary Verse. The emotions that the destruction of Swansea stirred in Watkins are elemental, crude, raw, unprocessed, lines not rarefied with theological symbolism or literary allusions, but seared onto the page with a furious clarity. “You were born when memory was shattered” Watkins writes, to his Godchild, in the most bitter line of the entire cycle: the ninth poem (“My lamp that was lit every night has burnt a hole in the shade”) is an act of memorial for this lost town, a cry of anguish against shattered memories, the violent erasure of a past now recalled with precision:

The burnt-out clock of St. Mary’s has come to a stop,

And the hand still points to the figure that beckons the house-stoned dead.Child Shades of my ignorant darkness, I mourn that moment alive

Near the glow-lamped Eumenides’ house, overlooking the ships in flight,

Where Pearl White focused our childhood, near the foot of Cwmdonkin Drive,

To a figment of crime stampeding in the posters’ wind-blown blight.I regret the broken Past, its prompt and punctilious cares,

All the villainies of the fire-and-brimstone-visited town.

I miss the painter of limbo at the top of the fragrant stairs,

The extravagant hero of night, his iconoclastic frown.Through the criminal thumb-prints of soot, in the swaddling-bands of a shroud,

I pace the familiar street, and the wall repeats my pace,

Alone in the blown-up city, lost in a bird-voiced crowd,

Murdered where shattering breakers at your pillow’s head leave lace. (9)

Watkins continues to address his Godchild in her cradle: “Listen” he says, “below me crashes the bay.” The imagery of the sea is as central to this poem’s symbolic economy as light and darkness. Swansea, burnt out in the arc of the bay, is soothed by the rhythms of the water: those who grow up in Swansea can often sense, innately and unconsciously, the importance of the sea to the phenomenology of the town. In Watkins’ poem it is an all-consuming symbol of destruction and regeneration, and permeates every single part of the piece in a way that is as repetitious and as varied as the tides. The sea is “a wave running over the Earth”, a hurling “sea-mass” “of pitiless history”, “the engulfed, Gargantuan tide” and “the magnificent, quiet, sinister, terrible sea”: an elemental force that is unpredictable, threatening and destructive. But it is also “that eternal Genesis”, “regenerate”, a “resurrection-blast” that “gave back a sigh”: an eternal source of renewal, comfort and vitality.

For Watkins, destruction contains renewal. Memories are classified by the physical details of the town: the clock of St Mary’s Church stopped dead at the moment of bombing (the roof had collapsed following fire damage); the Uplands Cinema (“Eumenides’ House”) in which he watched his childhood heroine Pearl White; his image of the artist Alfred Janes who lived above a College Street florist (“the painter of limbo at the top of the fragrant stairs”); and Cwmdonkin Drive, the childhood home of “the extravagant hero of night”, Dylan Thomas (10). Not every one of these memory traces was destroyed by the Luftwaffe, but like the eyewitness who declared “Swansea is dead” Watkins articulates a broader truth: the old, historic town with its delicate fabric of memory and association, its layers of time and experience, had been irrevocably eradicated by the fires that raged unchecked after three nights of bombing.

The wave runs over the earth, and also regenerates. Watkins returned to Swansea and Gower to recover from a nervous breakdown triggered while working in Cardiff: the town and peninsula became, in a very literal sense, a place of refuge for him. For most of his life he lived a regular, repetitious, comfortable existence as a cashier at the St Helen’s Road branch of Lloyds Bank, commuting every day from the clifftop village of Pennard (my mother would see him on the Number 64 bus when she got on at Bishopston in the 1960s). Watkins’ imagination was captured by this wider idea of Swansea: an expansive area incorporating the limestone and gorse cliffs of South Gower, with its gorgeous suite of sandy beaches and beautiful, secluded houses (his childhood home was one of these: Redcliffe, a Victorian house at the head of Caswell Bay that was demolished in the 1960s and replaced with a concrete apartment block). This was a town and a peninsula defined by the sea, and its regenerative effect was the dominant reality: both for his personal health, and for the post-war rebuilding of a modern port.

His 1962 ‘Ode to Swansea’ is a tribute to this vision of Swansea: a “bright town” (11) that emerges from the ruins of war:

Leaning Ark of the world, dense-windowed, perched

High on the slope of morning,

Taking fire from the kindling East:

This is the Swansea of light and water: a view down over the bay from the Victorian suburbs of the Uplands and the coiling streets and sprawling estates of Sketty and Townhill, over the

…shell-brittle sands where children play,

Shielded from hammering dockyards

Launching strange, equatorial ships.

The renewal of industry in the docks through the oil refinery which attracted the vast tankers that my grandfather would have known in some detail, working as a ship broker for Burgess & Co in 1962, provides, for Watkins, an image of the vitality of the town and its participation in the global pursuit of wealth and power. The poem is also infused with the perspective of a man of the Gower: gulls, pigeons, starlings, shags and cormorants all populate the picture, alongside the Mumbles Lighthouse, limestone rocks, Lundy and the fishing nets dropped off the coast. For Vernon Watkins, unlike Dylan Thomas, Swansea became a “loitering marvel” that contained multitudes: a lovely window onto a wide and teeming world, rather than a narrow, small, provincial place. “Prouder cities rise through the haze of time,” he wrote, “Yet, unenvious, all men have found is here.”

IV: ‘Return Journey’

In 1947 Dylan Thomas was commissioned to write a radio feature for the Home Service series ‘Return Journey’. At this time he was tempted to move to America, encouraged by his publisher James Laughlin who promised to look for a suitable house near New York, and very actively discouraged by his friend Edith Sitwell who tried to convince him to consider Switzerland instead, or Italy. This was an unlikely move: Thomas once told Laurence Durrell, “the highest hymns of the sun are written in the dark…If I went to the sun I’d just sit in the sun” (12). In February 1947, he went instead to a very cold and dark Swansea yet to be rebuilt and with the clock of St Mary’s still stopped dead at the moment of attack. This was the brutal winter that led to huge snow drifts and power cuts and shortages; broadcasting was limited, exposed cattle froze to death and the presiding Labour administration fatally damaged (they lost to the Conservatives in 1950). February, in particular, was the coldest month on record; the ruins of the town froze under layers of snow in conditions that recalled the nights of the Blitz six years before. Thomas was not exactly yearning for home at this time, but had been around Swansea in 1941, and the impact of the destruction on him was profound. Bert Trick met Dylan and Caitlin in the town centre the morning after the final raid and later wrote: “The air was acrid with smoke, and the hoses of the firemen snaked among the blackened entrails of what had once been Swansea market. As we parted, Dylan said with tears in his eyes, “Our Swansea is dead”” (13). Even more than the anonymous Evening Post eyewitness, the emphasis was highly personal: “Our” Swansea had been destroyed, a site of shared experience assumed to be universal but certainly not collective. The Nazis had destroyed his memories, the imaginative and emotional contours of his town; it was almost as if Hitler had aimed his bombs directly at Dylan Thomas. This was not the burning of an age: it was the razing of his youth. But as the ‘Return Journey’ script revealed, there was value in this perspective.

The recollections of ‘Return Journey’ go wider and deeper than the Blitz, although this event gives the script focus and also overshadows everything in it. The narrative perspective is suspended in time and space, a voice from the unconscious interrogating apparitions from Swansea past and present, drifting in and out of “the snow and ruin” (14). A barmaid, some Evening Post reporters, a Minister, a School Master, a Park Keeper, among others, collectively piece together impressions of Young Thomas chasing girls, drinking too much, filing useless newspaper reports, mooching around the promenade and sand dunes, climbing trees and cutting off branches in Cwmdonkin Park. Like Under Milk Wood, the medium allows a form that is fluid and overlapping, not bound by any conventional narrative devices or visual or spatial limitations. The texture of memory is key: shifting perspectives and dialogic cacophony; chaotic and vivid visual traces, triggers and clues. This drift of voices is filtered through Thomas’ dense poetic mannerisms: a barrage of alliteration and assonance; adjectives and verbs piled on top of each other or promiscuously modified (“he could smudge, hedge, smirk, wriggle, wince, whimper, blarney, badger, blush, deceive, be devious, stammer, improvise…” etc. 15). Memory is heightened with a poetic luster that conveys the distortions and poignancy of nostalgia.

This is punctuated by another technique that has a crucial and specific purpose: the careful recording of the names of vanished streets and shops and people dead and alive (“Mrs Ferguson, who kept the sweet-shop in the Uplands where he used to raid wine gums, heard her name in the programme, and wrote to say, ‘Fancy remembering the gob-stoppers’”, 16). Cecil Price later asked Thomas how he remembered all the lost shops that he lists: “‘It was quite easy,’ he answered. ‘I wrote to the Borough Estate Agent and he supplied me with the names’” (17). Like the scattered memories that Watkins crystallizes momentarily in ‘The Broken Sea’, this recording is a deliberate act of memorial, a motivation made explicit, and tragic, by a roll call of dead school contemporaries (“The names of the dead in the living heart and head remain forever. Of all the dead whom did he know?”, 18). The whole script is permeated with death, but the act of writing and the reading of names is an attempt to cheat it: to immortalise a lost world, at least partially. The inevitable failure of this attempt, for Vernon Watkins and Dylan Thomas, provides the emotional core of their acts of memorial.

Thomas had a more complicated relationship with this dead town than Watkins, for whom Swansea became a revitalising landscape and a refuge. For Thomas the town was a source of material inspiration that was the springboard for his flight out to the rest of the world. His recollection of the Kardomah Cafe gang through a litany of conversation topics and shared obsessions and references makes this point: “Einstein and Epstein, Stravinsky and Greta Garbo…Communism, symbolism, Bradman, Braque, the Watch Committee, free love, free beer, murder, Michelangelo, ping-pong, ambition, Sibelius, and girls” (19). The excitement of discovery and ambition that contact with the world ignites goes beyond the narrow confines of the locality in which you grow: for Thomas, Swansea is not necessarily enriched by this external world, but he is enriched by it despite the dampening provincialism of the town. The plan, like so many before and after, is to get out: “Dan Jones was going to compose the most prodigious symphony, Fred Janes paint the most miraculously meticulous picture, Charlie Fisher catch the poshest trout, Vernon Watkins and Young Thomas write the most broiling poems, how they would ring the bells of London and paint it like a tart.” The strain of nostalgia evident in ‘Return Journey’ is partly the affection of the escapee, looking back on what has been left behind, with all small town frustrations exorcised. But it is also a reaction to the violent eradication of the landscape of his youth, which robs him of an immediate physical environment upon which to reminisce. So much of such worth is easily lost: “The Kardomah Cafe was razed to the snow, the voices of the coffee-drinkers – poets, painters, and musicians in their beginnings – lost in the willy nilly flying of the years and the flakes.” For Dylan Thomas, in ‘Return Journey’, the Blitz was simply a more definitive, and cruel, expression of time.

V: The Anglo-Welsh

They went outside and stood where a sign used to say Taxi and now said Taxi/Tacsi for the benefit of Welsh people who had never seen a letter X before.

Kingsley Amis, The Old Devils

To have high esteem for a language you don’t actually use, while holding the one you do use in low esteem, is to be in a parlous mental and moral condition.

Conor Cruise O’Brien, Ancestral Voices

The Kardomah gang eulogised by Thomas and Watkins represented a creative sensibility that was part of an outward-looking, modern, anglicised urban and industrial culture clustered around the ports and coalfields of South Wales with related pockets in the Medieval Anglo-Norman enclaves of South Pembrokeshire and Gower. The productivity and the money that flowed from and into these areas was the source of a cultural and commercial dynamism that was noticed, momentarily, by the rest of the world. This was a crucial and even central component in the political and economic development of the principality and, therefore, any notion of Welsh identity and ‘nationhood’. It was a Welsh identity that was located in Swansea, Barry, Cardiff and Newport, with their commercial and mercantile character and their international links and contacts. It was also the Welsh identity of the Valley communities with their own internationalist links and aspirations fostered by the trade unions, the Labour party and Communist, Trotskyist and Syndicalist organisations, all traditions with no use for Welsh nationalism. As John Davies pointed out in his history of Wales, the most influential exponent of this world view, progressive from its own perspective, was Aneurin Bevan:

As he was convinced of the virtues of central planning, Bevan saw no necessity for that strategy to have a Welsh dimension. In his speech on 17 October 1944, he mocked the notion that Wales had problems unique to itself…Peter Stead has argued that, in the 1940s, it was Bevan specifically who frustrated any significant advance in the recognition of Wales; furthermore, he maintains that in subsequent decades every scheme for devolution would have to wrestle with Bevan’s notion of political priorities. (20)

The star poet of Wales and international exponent of Anglo-Welsh literature, woven well into the fabric of the contemporary Welsh heritage industry, was also hostile to Welsh nationalism and, even, the very confines of a Welsh identity. As Paul Ferris notes, for Dylan Thomas,

Wales was incidental. Thomas had no intention of being regarded as a provincial poet, and there was no substitute for living in London. It was only later that the question of Thomas as a specifically ‘Welsh’ poet arose; and when it did arise, he decried it…In 1952, in a letter to Stephen Spender, thanking him for his review of Collected Poems, he wrote, ‘Oh, & I forgot. I’m not influenced by Welsh bardic poetry. I can’t read Welsh’. (21)

Ferris qualifies this stark declaration by arguing for the Celtic character and technical influence of Welsh verse on Thomas’ strictly monolingual output. What cannot be argued is that, in common with other Anglo-Welsh writers, Thomas derived the bulk of his subject matter and inspiration from Welsh communities and characters and landscapes. This was a tendency dismissed savagely by Kingsley Amis, who met the poet in Swansea and considered him to be

a pernicious figure, one who has helped to get Wales and Welsh poetry a bad name and generally done lasting harm to both. The general picture he draws of the place and the people, in Under Milk Wood and elsewhere, is false, sentimentalising, melodramatising, sensationalising, ingratiating. (22)

The case against this tendency in Anglo-Welsh literature was given more measured and biting articulation in fictional form in The Old Devils, out of the mouth of Charlie: “Write about your own people by all means, don’t be soft on them, turn them into figures of fun if you must, but don’t patronize them, don’t sell them short and above all don’t lay them out on display like quaint objects in a souvenir shop” (23). From the scathing portraits of Caradoc Evans to the socialist ballads of Idris Davies and the pastoral mysticism of Vernon Watkins, this rootedness in the subject of Wales was both a weakness and a strength: but, more than anything, it helped to articulate the culture and aspirations of the English-speaking Welsh communities. Swansea was a central connection in this Anglo-Welsh artistic network, with its own creative cluster around Thomas, Watkins, Dan Jones and Alfred Janes, with flourishing satellites like the Swansea School of Art which produced the Surrealist painter Ceri Richards.

The Welsh nationalism that eventually found political form in Plaid Cymru defined itself in conscious opposition to this tradition. From inception, the focus of Welsh nationalism was language: this came to be the basic element of Welsh identity, and its legal and cultural resurrection the foundation of independent nationhood. The significance of this fact lies in the nature of the English-speaking regions of Wales, as described above. Welsh nationalism was at root a vision of Wales centred on the Welsh-speaking rural communities, the ‘Welsh Wales’ uncontaminated by the external and foreign influence of the modern industrial world. This conception of Welsh identity was regressive and insular, based on an artificial aesthetic of ruralism and a cult of the past augmented by Welsh folktales and Celtic legends, Bardic traditions and peasant superstitions. It was, basically, nativism, with a reactionary right-wing tendency at its core. Saunders Lewis was its authentic heart, a Roman Catholic partly responsible for bringing the ideas of French Catholic conservatism, Charles Maurras and Action française into the movement in the 1930s (24). By the Second World War, the Lewis faction was propounding an anti-democratic, extra-parliamentary platform that called for abstention from the ‘Imperial War’ against Hitler and a form of direct action that led to an arson attack on RAF Penrhos in 1936. Lewis was incarcerated in Wormwood Scrubs for this adventure and became a martyr for the Welsh cause, electrifying activist sentiment within the more militant Welsh-language communities. In the end, Welsh nationalism did not follow this violent course but it did re-frame the idea of Welsh nationality along the lines of language rights and a rural aesthetic that found expression in, for example, the Welsh Language Act of 1993 and the professional regeneration of the Eisteddfod. This would find its true home in the ‘liberal’ nationalism of a primarily middle class milieu attached to Plaid Cymru, the Church, the University of Wales and the provincial BBC.

This had an indirect effect on Swansea, which had no significant Welsh-language enclaves like Cardiff, and maintained a residual, resolutely anglicised culture which had been the basis for its civic and cultural identity during the years of industry. In reaction to the new cultural and political definition, or ideal, of ‘Welshness’, Swansea’s sense of self-identity crumbled alongside its vanishing industries in the 1980s and 90s. It had no clear way to orientate itself in this new, post-industrial Wales of the Assembly and the Language Act. Its major industrial history, like that of the Valleys, was reduced to perfunctory heritage trails and unenthusiastic school trips, or dismissed as a legacy of ecological disaster in the case of the Tawe and Swansea Valley. Swansea’s greatest cultural achievement — the outward-facing, expansive, experimental, anglicised coterie of the 1930s-50s — was eclipsed by the capture of Dylan Thomas for the Welsh cause, despite his own antipathy to nationalist sentiment and his own conflict with Welsh identity that both animated and distorted his work. Swansea, itself, was reduced by this new idea of the nation: both the complexities of the “two-tongued” city characterised by the anglicisation of its rural, Welsh-speaking settlers, and the Anglo-Welsh culture of its elite and middle classes that found literary expression in the work of Dylan Thomas and Vernon Watkins, were downplayed and even erased by this political project. This was a large part of the reason why, despite the apparent health of the Dylan Thomas industry, Swansea struggled to capitalise on or communicate the full significance of its own past: that past was now debased currency in Wales. Swansea, like Newport and Barry, was shortchanged by Welsh nationalism: nationalism was not interested in Swansea, or in its interests.

VI: The City

Swansea’s postwar history is a story of temporary renewal followed by steep decline. Following the Blitz, the local authority was faced with the task of rebuilding the entire central commercial area, a project which did not begin until 1947, in the months after the writing of ‘Return Journey’. In some ways, reconstruction never ended. The town centre was rebuilt in the clean concrete style of the New Town: the Kingsway became the wide central thoroughfare, a grey wind tunnel capped by a monolithic, Brutalist Odeon cinema. The town was, in a way, rebuilt in a manner befitting a modern city: a status finally bestowed by the Queen in 1969, by which time Swansea was rapidly losing all the elements that gave it national and even international prominence to begin with. Slowly the traditional industries were dismantled or relocated: the Llandarcy refinery was reduced to a specialist lubricating oil producer in the late 1980s, fully closing in 1998; Landore steelworks was converted into a small engineering factory in 1980; the Velindre tinplate works closed in 1989; finally, the Baglan petrochemical plant began to disappear from the Eastern horizon in 1994 and was gone by 2004. I grew up in the city from 1982, watching oil tankers lumbering impressively across the bay; by the time I left for university in 1996, they had, almost imperceptibly, completely disappeared from the channel. For the majority of people in Swansea, by this time, the change hardly registered at all.

So, the city redefined itself, reverting to an earlier ambition to create a glamorous seaside resort. “From the 1780s to the 1830s,” wrote J.R. Alban,

Swansea had great pretensions to becoming a seaside resort of some standing. ‘The Brighton of Wales’ or a ‘Welsh Weymouth’ were some of the comparisons made by contemporaries. During this period, the town was provided with bathing houses, bathing machines, public gardens, circulating libraries, public assembly rooms, theatres and a newspaper; in fact, all the accoutrements needed to make it a genteel and fashionable place or resort. (25)

Swansea did not become the Brighton of Wales. But, in 1982, the South Dock was transformed into a yacht marina, with hotels, cafes, bars and restaurants added throughout the decade. This was one of the first such post-industrial redevelopment projects in Britain and was, initially, a success, chiming with a new (definitely not parochial or Welsh at all) consumer and enterprise culture, ruthlessly mocked by Kingsley Amis in The Old Devils. Swansea, in this new world of services, leisure and tourism, stripped of its industrial identity, was more closely tied to the Gower than ever: one part became an adjunct of the other. The middle class commuter worked in Swansea but lived in Langland or Bishopston; tourists stayed at Oxwich or Llangennith but brought supplies or spent rainy days in the city. There was a new enterprise zone with a tropical hothouse, a multiplex cinema, and Toys-R-Us. The memory of Dylan Thomas was absorbed, mobilised, sold: the Swansea Year of Literature in 1995 was the apotheosis of this process. This redefinition of the city and its identity still stopped short at the border of Welshness and the politics of Welsh identity. This had not been an issue, or even at stake, in the city I grew up in, and it struggled to adapt to the new criteria of nationality. Like everywhere else at this time, the primary cultural influence was American: Dallas, Dynasty and Miami Vice could tell you more about the mores and imagination of the city of Swansea than the Mabinogion. Even as this self-image and those aspirations — dreams of Marbella or Miami played out on the set of the Maritime Quarter — dissipated in the ruin of recession, the imagination of everybody in my school still happened to be shaped by Beverly Hills 90210 and Baywatch rather than the medieval bards. This was the reality of the time and the location: there was no longing, or need, for a fabricated rural tradition. Swansea remained a modern city: open to outside influence, looking forward. As I wanted to show when I started to write this essay, if the city actually, fully, embraced this tradition it would find plenty to be proud of and even to feel confident about. It would, in fact, find something deeper and wider than the Dylan trail or constricting contours of Welsh identity: it would find the history of a town that let in and went out to the whole world.

- See Andrew Green’s blog post ‘Edward Thomas in Swansea’ for details of this meeting, with quotes taken from the Cambrian Post: https://gwallter.com/books/edward-thomas-in-swansea.htm

- Quoted in James A. Davies, ‘‘Under a Rainbow’: Literary History’ in Swansea – An Illustrated History, ed. Glanmore Williams (Christopher Davies, 1990) p. 221

- Nigel Arthur, Swansea at War – A Pictorial Account 1939-45, (Archive Publications, 1988), p.27 and pp. 34-5. This book has extensive details on all bombing raids on Swansea.

- Quoted in ‘Before the Industrial Revolution’ by Glanmore Williams, in Swansea – An Illustrated History, p.16

- David Boorman, ‘The Port and its Worldwide Trade’ in Swansea – An Illustrated History, p.77

- Dylan Thomas, ‘Reminiscences of Childhood (Second Version)’ in Selected Writings (Heinemann, 1970), p.3

- William Wootten, ‘In the Graveyard of Verse’, London Review of Books, August 9th 2001

- Vernon Watkins, ‘The Broken Sea’, The Collected Poems of Vernon Watkins (Golgonooza Press, 1986), pp.80-1

- Watkins, p.86

- James A. Davies, ‘‘Under a Rainbow’: Literary History’, p. 237

- Watkins, ‘Ode to Swansea’, p.285

- Quoted in Paul Ferris, Dylan Thomas (Penguin, 1978), p.223

- Ferris, p.184

- Dylan Thomas, ‘Return Journey’ in Dylan Thomas – The Broadcasts, ed. Ralph Maud (J.M.Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1991), p.183

- Thomas, ‘Return Journey’, p.185

- Ferris, pp.223-4

- Quoted in editorial note to ‘Return Journey’ by Ralph Maud, p.178

- Thomas, ‘Return Journey’, p.186

- Ibid., p.183

- John Davies, A History of Wales (Penguin, 2007), pps. 592-602

- Ferris, p.115

- Kingsley Amis, Memoirs (Penguin, 1992), pps.132-3

- Kingsley Amis, The Old Devils (Penguin, 1987), p.28

- Kenneth O. Morgan, Rebirth of a Nation: Wales 1880-1980 (Oxford University Press, 1982), p.256

- J.R. Alban, ‘Local Government, Administration and Politics, 1700 to the 1830s’ in Swansea – An Illustrated History, p.110

This is great ! My deep rooted affection bound up in the literary references so beautifully sourced here in this writing : the spectacular views still to be atmospherically found as you wander down Terrace Road where my mate Frank still lives after a thousand years with a vista like nowhere else . It will remain to me “the best sited town “ and has no need to compete culturally or aesthetically with anyone else !

LikeLike

Fantastic read Oliver. The writing flows easily and the information is absorbed without a feeling of patronising which spoils so many essays. It was fascinating to learn so much about Swansea.

LikeLike

Fabulously resonant writing elevating the memory of those wonderful writers. Merits wider readership in a literary journal e.g. LRB or even the New Yorker. I once wrote a feature for City Limits on the work of. Ceri Richards’ painter wife And was given a copy of Idris Davies’ poems by Neil Kinnock whom I interviewed years ago. A terrifically atmospheric, political read.

LikeLike

Pingback: ‘Time Reigns’: Vernon Watkins and Wales | Oliver Craner