Review of the Arrow Films box set Years of Lead: Five Classic Italian Crime Thrillers, 1973-1977

Mario Imperoli’s Like Rabid Dogs opens with a brutal armed robbery that takes place in the bowels of Rome’s Stadio Olimpico during the 1976 Serie A play-off between Lazio and Sampdoria. The film uses real footage of the match, a relegation fixture that was the first game in Italy to be patrolled by carabinieri with German shepherd dogs. On the pitch you can see the blonde mop of Luciano Re Cecconi, Lazio’s star player, who would be shot dead the following year by the owner of a jewellery shop in Rome, “a victim of the same violence we see in the movie,” as film critic Fabio Melelli put it. The original screenplay was inspired by the Circeo Massacre, a case of three middle class students who raped and murdered two girls in Lazio the year before and the lurid details of their crimes seep into the sleazy atmosphere and class dynamics of the film itself. Like Rabid Dogs is the product of an imploding society: it doesn’t just reflect the world it portrays, it belongs to it.

In an essay written for the Arrow Films box set Years of Lead, which contains a pristine restoration of Like Rabid Dogs, Troy Howarth roots the 1970s cycle of Italian crime films in the 1960s thrillers of Carlo Lizzani, suggesting a loose overlap with neorealism that is partly a matter of politics and partly technique. Imperoli’s use of footage from a real football match is one example of this and his habit of filming car chases in live traffic in the middle of Rome is another: Like Rabid Dogs is filled with spectacular chases shot without permission from the city authorities, supervised by one of the top specialist stunt drivers working in Italy at the time, Sergio Mioni. This was the same year that Ruggero Deodato shot a motorbike pursuit for Live Like a Cop, Die Like a Man in the Roman rush hour before the police even knew what was happening. Like Lizzani, Deodato began his career as an assistant to Roberto Rossellini and would later combine the tricks of neorealism with the excesses of the mondo documentary to explosive effect in Cannibal Holocaust. The chaos and lawlessness that Imperoli and Deodato put on screen was an integral part of the way these movies were actually made — they were conditioned by the world they depicted.

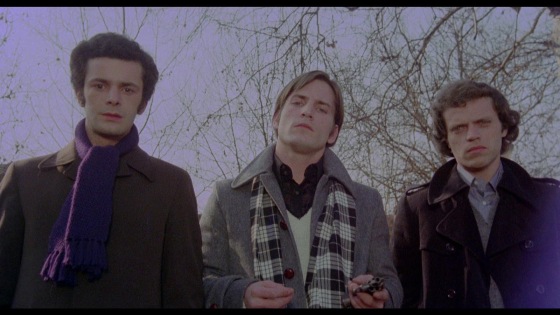

The death spiral of the First Republic was the grand Italian drama behind all of this. The source of the crisis was external, but the effects were strictly local. In his 1975 shocker Savage Three — another film in the Arrow set — Vittorio Salerno took cues from A Clockwork Orange, but replaced literary concerns with the parochial details of a national conflict. The location of Turin was key: the home of Fiat and the Agnelli network, it became a symbol of Italy’s economic miracle. For the same reason, it was also the heart of industrial action and Red Brigade terror during the Years of Lead. From this point of view, then, the city was a symbol of Italian disunity — or, as Emilio Gentile described it, the fragility of the myth of the nation. Turin had been the first capital of Italy and unification was led by the Piedmontese, who imposed their own laws and institutions on the rest of the country. The south resisted ‘Piedmontization’ from the very beginning and this sense of historic resentment was intensified by mass migration to the industrial north during the postwar boom. Southern workers, languishing on low wages in overcrowded apartments, felt alienated and despised here. This was the city of Savage Three: a highly combustible, racially charged slum.

For Salerno, Turin’s faded streets, piazzas and parks provided the perfect stage for an outburst of nihilistic violence led by Ovidio Mainardi (Joe Dallesandro), a slowly unravelling psychopath employed in a computer processing plant on the outskirts of the city. His friend Pepe (Guido de Carle) is a Sicilian who lives with his extended family in a packed apartment; like the Parondis in Visconti’s Rocco and his Brothers, he is dangerously alienated and adrift in this new urban environment. The Turin shown in Savage Three is awash with anti-southern prejudice: the Sicilians and Calabrese packed onto factory floors are considered racially inferior and prone to irrational violence by the city authorities. When Ovidio and his accomplices brutally murder a prostitute and her pimp they leave the bodies hanging from the Monumento al Conte Verde and the gruesome tableaux is described by Inspector Santagà (Enrico Maria Salerno) as “a defamation and offence to the sacred legacy of the nation.” Santagà’s comment is both ironic and bitter: being a southern migrant himself, he is alert to the racism of his colleagues. For them, the crime wave is the inevitable result of southern migration and a symbol of the political bankruptcy of the nation (these are the future foot soldiers of Lega Nord). Santagà, however, immediately sees the crimes for what they really are: not the result of genetics or beliefs, but blank outbursts of boredom and despair.

In Savage Three, Turin looks like a city that has been defeated: the football stadium, the streets and the buildings are visibly broken, exhausted, unclean, crumbling. This is not the Turin celebrated for its elegance and ceremony, but a 1970s urban sprawl which Salerno depicts as a human trap: citizens crowded into constricted living and working spaces that create the conditions for intolerance, conflict and murder. And this is not just the city: everything looks depressed and drained, in line with the common visual tone of the poliziotteschi. In these films, the sky is invariably blank and grey, a featureless ceiling of drab cloud that creates a simultaneously flat and oppressive atmosphere; the saturated colours of the gialli and the seductive monochrome of neorealism are replaced by an ugly, washed-out tonal range. The poliziotteschi city is a bleak, malignant place, where all human relations are negative and most human interactions are violent. Turin has unique divisions caused by southern immigration and its racist reaction, but the general malaise is shared across the country. Fernando di Leo’s Milan is not defined by beautiful arcades or the Duomo di Milano, but by rotting ghettos that run alongside the canals, grey rain-drenched piazza tiles and warehouses where corpses wait a long time to be discovered. Umberto Lenzi’s Rome is not the Rome of romantic weekends and ancient ruins, but a dirty and congested labyrinth of squalid flats, dank alleys, damp staircases, bleak wasteland and scrappy tenement rooftops, settings for various acts of torture, rape and murder. Enzo G. Castellari’s Genoa is perhaps the most desperate of them all: a terrifying, feral, decadent city, rotten with vice and corruption, festering on the edge of the Ligurian sea. The fate of Italy’s cities in the 1970s is encapsulated by some of its most famous crime titles: Fernando di Leo’s Milano Calibro 9 (1972), Marino Girolami’s Violent Rome (1975), Lenzi’s Gang War in Milan (1973), Rome Armed to the Teeth (1976) and Violent Naples (1976). The cities are the focal point of Italy’s crisis: the piazzas and train stations are bombed and the banks are robbed, while criminal gangs and rogue policemen rule the streets and citizens are terrorised by random acts of slaughter. Perhaps the definitive Italian crime title is the one that Sergio Sollima gave his 1970 hit man melodrama, Città violenta, even though that film is set in New Orleans. The cities are violent places that condition their inhabitants to commit more violence: an endless, animalistic cycle that Salerno depicts so well in Savage Three.

Lucio Fulci once claimed that “violence is Italian art” and the art of the poliziotteschi is a very Italian aestheticization of violence. Even the ugliness has style. This is why these films always tread a fine line between exploitation and art, nihilism and morality. The films of Imperoli and Salerno are perfect examples of this: they can be hard to watch, but they are impossible to dismiss. The violence is extreme, but makes its point for this reason. The question of motive is always present, but usually has no clear answer. In Savage Three, Santagà is the only one who understands that the brutal acts instigated by Mainardi are a response to the alienating conditions of contemporary Turin. In Massimo Dallamano’s Colt 38 Special Squad (1976) the motivation for the crime is key but also ambiguous. At first the operation planned by the Marseillaise (Ivan Rassimov) seems like a simple case of common theft, albeit conducted on a grand scale, but as Rachael Nisbet shrewdly points out in her accompanying essay to the Years of Lead set, there is something more sinister at work:

While the motivations of the common criminal are clear, the Marseillaise is a more complex individual; a man driven by a certain sense of madness and anarchic glee…his perverse sadism and disregard for life suggest that his actions are motivated by something far darker than the driving factors of vengeance and retribution…

Mainardi and the Marseillaise are both nihilists but the scale of the Marseillaise’s plan is more ambitious than the spasm of violence unleashed by Mainardi. He wants to inflict a grievous wound on Turin and live to see it; the motivation of wealth does not adequately explain this instinct. This is more than simply a plot point, or an absence of one: it taps into the atmosphere of uncertainty that defined the atrocities of this period, and was never adequately resolved.

Italian political culture in the 1970s was so convoluted and secretive that when Henry Kissinger claimed that he did not understand it nobody thought he was joking. In 1988, the Italian state set up the Commissione Stragi (‘The Slaughter Commission’) tasked with uncovering the truth behind the bombings that occurred between 1969-88 and had been variously attributed to the Red Brigades, anarchists, neofascists and the CIA. Predictably, it failed to remove the opacity of the period or provide any real psychological closure. The scenes of carnage that follow the bombings of Turin railway station and market in Colt 38 Special Squad stand out for their graphic brutality and emotional poignancy. Dallamano shot the film only four years after the Piazza Fontana bomb, so these scenes pierce his movie like unmediated expressions of national post-traumatic stress: they were not shot for thrills, but carry a lot of psychological weight and evoke still raw memories. What can’t be answered in the film, and what could never be effectively answered in real life, is the reason for all of this destruction and cruelty: the Slaughter Commission could not solve it and Dallamano refuses to provide a neat conclusion in the character of the Marseillaise. The ambiguity of the violence and the veil that fell over the most extreme events that ripped through Italy in the 1970s are a central part of the poliziotteschi world view: if nobody can fully account for this violence, then perhaps it is simply endemic to the fragile and conflicted Italian nation, something that can never be solved.

But Colt 38 Special Squad also fulfills another function common to these films: it provides a psychological outlet, a form of mass catharsis. The disintegration of Italian society was intensified by the prominent role of organised crime, black markets and corruption in a free falling economy. The Italian crime films give voice to the pervasive feeling that the Italian authorities had fallen behind the criminal gangs, even if they were not already hopelessly compromised by them. Fear and helplessness combined with anger; the films responded with bleak cynicism and tales of rough justice. Quite often the stories revolve around detectives or special units within the police force going rogue, using unorthodox and even illegal methods in order to catch or destroy criminal antagonists. The Special Squad in Dallamano’s film is put together to crush the crime wave that has tipped Turin into near anarchy; they are given licence to use Colt 38 revolvers and pursue their targets with freedom that stops short of murder (or is supposed to). It is only by going beyond the limits of legal authority that the Marseillaise is finally stopped. Stelvio Massi’s 1977 Highway Racer (another film in the Arrow box) pays homage to Armando Spatafora, a member of Rome’s Squadra Mobile whose 1960s exploits were legendary. In the film the young Squadra Mobile driver Marco Palma (Maurizio Merli) soups up a boxy Alfa Romeo and demands a Ferrari from his boss, the Spatafora doppelganger Tagliaferri (Giancarlo Sbragia), because “I don’t want to lose before I begin.” Retaking the advantage is key and requires special measures. Merli excelled at playing rogue cops like Inspector Tanzi in Umberto Lenzi’s frantic and stylish films Rome Armed to the Teeth and The Cynic, the Rat and the Fist (1977), characters that pushed their job description beyond law enforcement into the realms of vigilantism. These were cops who had not been given any special license, but had simply gone off the rails, driven to rage and despair by inability to deliver justice. The poliziotteschi, with their special squads and vigilantes, gave Italians an alternative reality in which this imbalance was finally redressed and Italian society redeemed, however morally questionable that redemption was.

But they also provided a troubling critique and quite often without any release or redemption. Italy in the 1970s was paralysed by corruption and this was more insidious than terrorism and crime because it undermined any sense of security in state and local authority and, even, any trust in the reality of appearances. Vittorio Salerno’s 1973 film No, the Case is Happily Resolved is the one entry in the Arrow set that focuses on this total breakdown in trust, with a narrative so pure in its inexorable and dire logic that it almost presents a parable for the Italian crisis. The corruption in this case is psychological and sexual: at the opening of the film Professor Eduardo Ranieri (Riccardo Cucciolla), a quiet and respectable maths and physics teacher, brutally beats a Roman prostitute to death in a reed bed outside of the city. Fabio Santamaria (Enzo Cerusico), a young working class man who witnesses the murder, eventually finds himself framed, arrested and jailed for the crime after a relentless series of misjudgments that recall the fate of Richard Blaney in Hitchcock’s Frenzy (1972). Santamaria makes the fatal decision not to report this crime and to try to cover up his presence at the scene, largely because he distrusts and even fears the police. This instinct proves correct: the police believe Ranieri because of his position and his appearance, while jailing Santamaria with only a cursory investigation. Murderous and possibly perverse impulses are veiled by the professor’s exterior presentation and this is compounded by an official corruption that renders the police ineffective and even dangerous to defenceless citizens. All the authority figures in this film either conceal their true identity or cannot be trusted to do their jobs safely: all certainty is therefore undermined and Italian society is shown to be based on deception and illusion, a place where reality is inverted and nobody is secure.

The Italian crime films of the 1970s did not just reflect their own society, then, but made an active contribution to the atmosphere and dynamics of the Italian crisis. The poliziotteschi cycle played out in the shadow of real and relentless atrocities committed by political and criminal groups and state actors. The films did not always or necessarily comment on any of this, but political violence and social degeneration were part of their visual and thematic fabric. The Italian peninsula was tense, fragile and paranoid, its traditions and moral base challenged by the rise of industrial cities, mass consumerism and the cultural influence of America. As Emilio Gentile noted, all of this occurred in the ruins of the myth of the nation, at a time when “Italians were experiencing a mass anthropological revolution in their attitudes and behaviours” and the state was being contested by the existential conflict between Catholicism and Communism. In this context, popular culture had a crucial role to play in shaping narratives, ideas and emotions on a large scale and Italian artists seemed to instinctively grasp this. This is not to assign responsibility for any specific events to these films but to accord them their due social and cultural power, even at the low level of the regional cinema circuit. It so happened that the Italian crime films of the 1970s had a more profound and immediate relationship with their world than any of the more fêted artistic products of the time. The importance of Arrow’s Years of Lead set is that it recognises this and therefore values the films at their true worth.