I: ‘Welshness’ and Poetic Identity

For Vernon Watkins, success could not be measured by book sales or critical acclaim; he paid attention to literary trends, but reserved polite disdain for fashionable writers, “contemporary poets” and the literary power brokers he considered misguided and even corrupt. He broached this subject with his hero Yeats when they finally met in 1938 and recorded the response in his long poem ‘Yeats in Dublin’:

My quarrel with those Londoners

Is that they try

To substitute psychology

For the naked sky

Of metaphysical movement,

And drain the blood dry.All is materialism, all

The catchword they strew,

Alien to the blood of man. –’

One ranting slogan drew

That “Poetry must have news in it”:

The reverse is true.’ (1)

This was recollected with approval — it was Vernon’s own opinion, too. The primary target here was Auden, a poet he admired as a craftsman but could not abide as an ideologue. His antipathy to the prewar influence of Christopher Isherwood and his coterie was more personal. Isherwood was an old friend from Repton College who fell out with Vernon at Cambridge and would publicly humiliate him in the caricature of Percival, the “gullible” and “gushing” ingénu of Lions and Shadows (2). Personal temperament, artistic principles and private wounds contributed to an uncompromising ideal that Vernon created for himself — the poet dedicated to his muse, scorning all public and didactic functions. Once his own poetic identity had been conceived in this way he could accept almost anything, including the silence of critics, pathetic book sales and the day job at Lloyds Bank. This was a fundamentalist creed, an act of passive resistance to the vanities and appetites of his more successful contemporaries:

One critic, I believe, said — perhaps it was of my last book — that each new book of Vernon Watkins is more old fashioned than the last. Well, of course I’ve never cared much about fashion. I think a poet has to think in terms of centuries. It’s a critic’s business to think in terms of decades and to sort out what is happening. Fundamental truths don’t change and I’m a metaphysical poet. I’m entirely concerned with those. (3)

The critics, for their part, remained unmoved by this slight and Vernon’s revolt against fashion went largely unnoticed. There was always a trace of pique in these statements of artistic protest but they were nevertheless authentic. The independence that Vernon felt from ‘the literary scene’ was genuine and consistent. This strength of resolve was rooted in the psychological breakdown he experienced at the age of 23, an episode he described as “a complete revolution of sensibility” that made all of the poems written up until that point obsolete and set a whole new course for his work.

This “revolution” defined Vernon’s ultimate theme (“I could never again write a poem which would be dominated by time,” 4) and, compared to this, temporary success on the London scene did not seem very important or particularly relevant. Despite this, he was not an artistic recluse and made periodic submissions to T. S. Eliot at Faber & Faber which led to the publication of seven volumes of his poetry between 1941 and 1968. They did not sell well, partly because the style consistently ran against prevailing poetic trends and ignored contemporary innovations. It’s a style that remains a barrier to this day and so critical interest tends to focus on Vernon’s position as a prominent Welsh or Anglo-Welsh poet, or simply as a friend of Dylan Thomas, in whose shadow he remains. A more refined approach still falls short, as those seeking the true ‘Poet of Gower’ also tend to leave disappointed. In his work contact with the land can seem tenuous and lost in abstraction, yet the Gower fed his imagination and Wales gave him roots. When he began to write seriously again, South Wales would provide him with the physical and symbolic grounding that he needed to begin anew. His first volume opened with two poems located in the mining towns of the valleys and closed with a ballad inspired by the New Year ritual of the Mari Lwyd. During the period of recuperation that followed his breakdown, Vernon roamed the Gower coast and developed an intimacy with its landscape that would saturate his work. But did any of this make him a “Welsh” poet? Born in Maesteg to Welsh-speaking parents, he lived and worked for most of his life in Cardiff, Swansea and Gower and this made him, at least, a Welshman who was also a poet. The correct, and more complex, question is: was he a poet of Wales?

There is very little evidence in his own writing and in the recollections of his friends that he considered Wales to be a “cause” that he needed to or should write for. His own answer to this question was precise: he called himself “a Welsh poet writing in English” rather than an ‘Anglo-Welsh poet’ and the significance of this was language. Vernon was not a Welsh-speaker or reader and his connection to the early literature of Wales, whether it be the Mabinogion, Taliesin, Aneurin or Llywarch Hen, was limited to childhood memory and English translation. This provided just enough to feed his imagination and, later, some of his poetry, but, as his close friend Glyn Jones pointed out, “it is vain to look in his work for the influence of Welsh-language poetry, ancient or modern” (5). He didn’t adopt the extreme rejection of ‘Welshness’ itself that became common in the anglicised South East, but this was the world in which he grew up and which he knew best. A generation of children raised in South Wales had not been taught any Welsh at all; even their Welsh-speaking parents often considered their native language to be a parochial and archaic irrelevance with no place in the dynamic industrial society being forged around them. Vernon’s mother, specifically, left rural Carmarthenshire to be educated in London and then Bolkenhain in the Sudetenland; rather than teach her son Welsh, she encouraged him to learn German, a language in which he became fluent and enabled him to produce translations of Holderlin, Heine and Goethe. Even though he expressed some regret about not knowing Welsh he never actually attempted to learn it, although he did make the effort to learn French, Italian, Spanish, Hungarian and Latin to complement his already fine German.

Vernon was a talented linguist with no personal or professional use for what others considered to be his stolen native tongue. “Wales is my native country,” he wrote, “and English the native language of my imagination” (6). Roland Mathias would later claim that Vernon had been “deprived” of his Welsh heritage by losing the language, “the common fate of the first main generation of Anglo-Welsh writers” who were the unwitting victims of petit bourgeois “snobbery” and an English assault on Welsh culture (7). To the extent that this was true, Vernon more than compensated for it by his fluency in European literatures and his participation in the outward thrust of the culture of South Wales at this time, a direction of travel shared by Marxist colliers in Tredegar and Rhymney and the middle class professionals of Swansea, Cardiff and Newport. The actual influence of the Bardic tradition and the Welsh language on his work was, by Vernon’s own account, a matter of rhythm and sound: “my verse is characteristically Welsh in the same way that the verse of Yeats is characteristically Irish…because rhythm and cadence are born in the blood” (8). Like Dylan, whatever ‘Welshness’ was there existed in the sound effects that shaped an English verse otherwise dominated by Blake or Yeats or Hopkins. Vernon’s widow Gwen Watkins would later claim that he

never wished to write in Welsh, because the richness of the English language satisfied him completely; and though he saw no meaning in a narrow nationalism, and loved many countries, Wales always held a chief place in his heart. (9)

Wales was important for many other reasons, but the poetic traditions that he really identified with were not Welsh at all: they were English, German, French and, in the form of Yeats, Anglo-Irish. The ‘Welshness’ of his poetry was evident in the cadence, traditions and landscapes that he used, but these did not define the total ambition of his work which was aesthetic and spiritual rather than ideological or material. He was not extolling the land: he was trying to overcome the tyranny of time.

It was left to an English critic to mistake Vernon for a Welsh bard. Kathleen Raine was a prominent champion, describing him as “the greatest lyric poet of my generation”, and, as critical accolades of any kind were relatively rare for him, he appreciated the support. But the problem was that her view of what he was actually doing was false: the image of Vernon she painted was a Celtic mirage that provided greater insight into her own fantasy world than the poems she was writing about. For Raine, Vernon was “an heir to the bards”, a poet of “the Celtic tradition” and “the spiritual knowledge of the Druid tradition” (10). While she acknowledged his expertise in German and French literature and his immersion in English culture, to her the “bardic tradition” was the thing that really mattered in his work. She was able to discern the influence of Eliot on Watkins, but found Yeats to be far closer “in his understanding that tradition is not anything and everything that has historically occurred, but a few heroic and religious themes, passed on from age to age” (11). She was partly right about this, but perhaps did not fully appreciate the extent to which the nationalist impulse behind the revival of Irish legends and myths was precisely the thing that Vernon rejected in Yeats. This would lead her to take his talk about rhythm being in the blood to its logical conclusion by identifying “a voice…of the race” in his verse and attributing his “intricate rhythms and assonances” to an intrinsic and immutable Celtic identity that he not only (in her view) consciously adopted, but could not escape from even if he wanted to. But this doesn’t really seem to have been what he had in mind. It was certainly too much for Roland Mathias, Raine’s editor at the Anglo-Welsh Review, who accused her of “not having read his work carefully enough” (12) and pointed out that “there is very little evidence that the bardic spirit had any place in Vernon Watkins’s approach to poetry” (13).

Watkins did adopt the legendary figure of Taliesin in six of his poems, which possibly set Raine down this wrong path in the first place, but these do not do enough to justify her claim that “the Lay of Taliesin” constituted “his classical ground” (14). In fact, he did not so much adopt as adapt: Taliesin gave Vernon a poetic device that he could use in the service of his own obsessions. This had almost nothing to do with ancient knowledge, the Druid tradition or the bardic inheritance and everything to do with his own philosophical project, for which he took everything he could. Mathias notes that Vernon came to associate Taliesin with Gower based on a tenuous connection with its own source and uses:

In Lady Charlotte Guest’s Mabinogion (1877) there are extensive notes of the text account of the life of Taliesin: one of these quotes a document from the Hafod Uchtryd Collection which, while following Anthony Powel of Llwydaeth in making Taliesin the son of Saint Henwg of Caerleon and having him captured by the Irish while coracle fishing in the course of a visit to the court of Urien Rheged at Aberllychwr, alleges that, escaping, he was cast ashore on the coast of Gower rather than at Aberdyfi. (15)

Vernon used this slender reference as his starting point, a fixing point, for his Taliesin poems: it allowed him to place the legendary poet in the landscape he knew best and could interpret. Mathias is particularly good at showing how Watkins was able to fit Taliesin “the time conqueror” into his own “post-Blakean spirit of cosmic mystery” and “practical Christianity” in poems like ‘Taliesin in Gower’ and ‘Taliesin and the Spring of Vision’. A shard of Mediaeval biography, Heroic poems, the figure of the shapeshifter and the prophet are incorporated into a developing theological superstructure with no regional or nationalist relevance. Vernon’s adoption of Taliesin did not add anything substantial to the old heritage but became a vessel for something altogether new and personal.

For example, ‘Taliesin in Gower’ presents a “vision” of “the landscape to which I was born” where the gulls, curlews, kestrels, larks, lapwings and herons of Gower are “holy creatures” that “proclaim their regenerate joys” (16). Nature is encountered as a script, a recital (“the script of the stones…the tongue of the wave”) that is played out on the “mighty theatre” of Oxwich, Pwlldu and Three Cliffs Bay. Taliesin defines his role as an interpreter of this natural drama, striving to “loosen this music” of nature, to “celebrate…marvellous forms” and “make manifest what shall be.” ‘Taliesin in Pwlldu’ unites this neo-Platonism with a more pragmatic Christian vision:

My Master from the rainbow on the sea

Launched my round bark. Through darkness, trailing hands,

I drifted. Wave-gnarled images of gods

Floated upon the whale-backed water-plains.

I looked; creation rose, upheld by Three. (17)

This reconciliation is advanced in ‘Taliesin and the Spring of Vision’, the most explicit exposition of Vernon’s personal philosophy:

Life changes, breaks, scatters. There is no sheet-anchor.

Time reigns; yet the kingdom of love is every moment,

Whose citizens do not age in each other’s eyes.

In a time of darkness the pattern of life is restored

By men who make all transience seem an illusion.

Through inward acts, acts corresponding to music. (18)

If time reigns, then it can be tempered by duality and regeneration and, finally, defeated by human memory and art: “the measure of past grief is the measure of present joy” and, so, “time’s glass breaks, and the world is transfigured in music.” This Taliesin is a prophet who can penetrate the secret patterns of nature and reveal the final triumph over time that finds symbolic form in the natural world and poetry itself (“the soul’s rebirth”). The land to which Taliesin “belongs” and with which he “identifies” is not simply the Gower coast to which his wooden boat returns, but an interior landscape in which he can trace the abstract, hidden patterns of nature and therefore God.

II: Swansea and Memory

There is no Welsh ‘tradition’ to which Vernon truly belonged, other than a sketchy ‘Anglo-Welsh’ lineage traced by Mathias, Kiedrych Rhys, Glyn Jones and Raymond Garlick, a literary identity that he himself categorically rejected. But there was one Welsh group that Vernon did identify with and this was no tradition at all, nothing like a movement and barely existed as a tendency. To the extent that it did, it displayed no particular interest in the parochial concerns of local heritage or tradition.

The “gang” that met in Swansea’s Kardomah Cafe before the Second World War was hardly anything more than a group of very talented friends with wide interests and varied talents. This was a largely middle class set with mild bohemian pretensions that was well represented by Dylan Thomas and Vernon, both products of the thriving, increasingly confident and self-enclosed society of the affluent Swansea bourgeoisie. Vernon was the son of a bank manager and Dylan the son of a grammar school teacher; they were both raised in the elegant suburban splendour of the Uplands, safely removed from the dirt and danger of the slums and docks, watching over a fiery landscape of industrial production. If there is one thing that the ‘Kardomah boys’ all shared then it was their refusal to set limitations on their intellectual or artistic ambitions. Their bourgeois Swansea enclave — and even Wales itself — was simply too small to contain them. It is where they came from, where they lived and where they usually worked, but they were always scanning wider cultural horizons and plotting their escape. Their conversations had a cosmopolitan range that revealed their expansive aspirations and was captured by Dylan in Return Journey: “Einstein and Epstein, Stravinsky and Greta Garbo…Communism, symbolism, Bradman, Braque, the Watch Committee, free love, free beer, murder, Michelangelo, ping-pong, ambition, Sibelius, and girls” (19). Inevitably, they would look back on all of this with a mixture of nostalgia, idealism, even awe, and the destruction of the old cafe on Castle Street during the Swansea Blitz hit them hard, especially Dylan, maybe the most sentimental of the lot.

For Vernon, Swansea had multiple and overlapping points of significance: it is where he first discovered the treasures of English poetry; where he first watched his heroine Pearl White plunge to her death on the Uplands Cinema screen; where he first met Dylan (like many others, he would forever associate Cwmdonkin Park with his dead friend); and where, in the Kardomah, he came closest to finding an artistic community in whose company he felt like he belonged. For those reasons and others too, Swansea became a positive place for him. In his 1962 ‘Ode to Swansea’ he even treated the town’s industrial legacy in positive terms, eulogising the “merchants, traders, and builders” moving through the streets and the “hammering dockyards/launching strange equatorial ships” (20). Swansea, “dense-windowed, perched/high”, remained “anchored” by its own “myth”: a “Leaning Ark of the world…taking fire from the kindling East” and linked into a maritime trading empire that stretched far beyond the Devon horizon. This was a time when Swansea was still a vital place: not just in terms of its cultural and social vibrancy but also industrial power. The combination of coastal ports with coal fields and copper, iron, steel and tin, had, by the time Vernon was born, produced one of the first developed industrial societies in the world. While this was not to everybody’s taste and provided the most powerful challenge to the nationalist focus on the Welsh language and rural communities, it was also the most effective catalyst for wealth creation, political development and social progress the country had ever witnessed. Swansea was in the vanguard of this industrial drama and it was this town that Vernon chose to mythologise. The industry and the ships, the smoke and the noise, were all part of its culture; in fact, they were the reason it existed in the ambitious, dynamic form that he saw in the artistic coterie that assembled at the Kardomah.

So, in the symbolic network of his poetry, Swansea took on eternity:

Would they know you, could the returning ships

Find the pictured bay of the port they left

Changed by a murmuration,

Stained by ores in a nighthawk’s wing?Yes. Through changes your myth seems anchored here.

Staked in the mud, the forsaken oyster beds

Loom; and the Mumbles lighthouse

Turns through gales like a seabird’s egg.

That emphatic “yes” serves a dual function: to confirm change wrought by time and to affirm the eternal and indestructible identity of the town itself. Here time is manifest in seasons, cycles, the rhythms of commerce and industry, the daily routines of work and the turning of the Mumbles lighthouse, but the eternal and unchanging identity of the town itself ultimately defeats its passage. On a personal level, it would serve this function too, becoming a site of memorial on multiple levels. During three nights in February 1941 the centre of the town was almost entirely razed by German air raids (see my previous essay ‘The Town Blazing Scarlet’: Swansea’s Blitz) and the landscape of Vernon’s youth and early adulthood changed forever. His long war poem ‘The Broken Sea’ was, in part, a eulogy for this erased landscape that also attempted to immortalise its physical landmarks in verse. These were, for Vernon, the landmarks of memory, both collective and individual:

Child Shades of my ignorant darkness, I mourn that moment alive

Near the glow-lamped Eumenides’ house, overlooking the ships in flight,

Where Pearl White focused our childhood, near the foot of Cwmdonkin Drive,

To a figment of crime stampeding in the posters’ wind-blown blight.I regret the broken Past, its prompt and punctilious cares,

All the villainies of the fire-and-brimstone-visited town.

I miss the painter of limbo at the top of the fragrant stairs,

The extravagant hero of night, his iconoclastic frown. (21)

When he is writing with this level of concrete, physical clarity it is usually to enrol nature in his thematic universe. In this case, he comes close to doing what he usually avoids: the poem almost serves a public function by creating a memorial for a lost town littered with images that defined it. But then these landmarks are also personal: the Uplands Cinema screening Pearl White serials, Cwmdonkin Drive (home to the young Dylan) and the College Street flat of the painter Alfred Janes. This is not only a memorial to a physically destroyed town, but also to the loss of the Kardomah gang, dispersed by ambition, opportunity and the passage of time rather than Luftwaffe bombs.

His memories of the town also became entwined with the memories of Dylan Thomas. He would write a series of poetic eulogies to his friend, not all necessarily tied to Swansea, although he could never write about the town without some direct or occluded reference to Thomas. In the poem ‘A True Picture Restored – Memories of Dylan Thomas’, Cwmdonkin Drive and the park become the site of a slightly overwrought origin myth:

Climbing Cwmdonkin’s dock-based hill,

I found his lamp-lit room,

The great light in the forehead

Watching the waters’ loom,

Compiling there his doomsday book

Or dictionary of doom.More times than I can call to mind

I hear him reading there.

His eyes with fervour would make blind

All clocks about a stair

On which the assenting foot divined

The void and clustered air.That was the centre of the world,

That was the hub of time…(22)

For those familiar with the biographies of the two men and the physical reality of the Uplands, this is not obscure at all: Vernon is writing about Dylan’s childhood bedroom, in which he lived and where he wrote most of his early poems while working as a reporter for the Swansea Evening Post. This is where Vernon first met Dylan and shared something like a moment of sublime recognition, a poetic epiphany: at a certain time, artistically and emotionally, this was the centre of the world for him. Maybe it was ground zero for Swansea’s artistic renaissance.

Being engaged in a personal war on time it was inevitable that Vernon would become a serial eulogiser: it was one of the most powerful weapons at his disposal. Dylan was only one of his subjects and many other poets and friends received the same treatment. In each case this served a specific emotional purpose, but it ultimately served the same end: the attempt to conquer time. Whether fixing the image of Dylan writing in his bedroom or composing visual images of a town flattened by the Nazis, memory and the act of memorialistion became potent weapons in this psychological battle. Before his breakdown, he had treated poetry as a romantic vocation, but afterwards it would become a means to overcome the otherwise inescapable reality of death. Places and people were part of this struggle rather than subjects in their own right.

In a talk titled ‘The Place and the Poem’ Vernon directly addressed the relationship between place and memory in his work. “Memory itself works very intricately,” he noted,

episodes and half-episodes are photographed obliquely: a hundred thousand moments of transience are recorded in minute detail. At first they look like small coloured pictures stuck in a scrap-book by someone with no discrimination. The Swansea of my childhood’s scrapbook, so much of which has been destroyed, is full of such pictures. (23)

Among the most potent of these memories was the silent movie actress, Pearl White:

The first Great War had broken out, and we were full of stories of heroism; but the heroine of many of those serials was Pearl White, the American actress who could express horror with wider eyes than anyone else, and who really used to throw herself off buildings into rivers and risk her life in the making of the films. She was always my heroine, and I looked to her to do all the heroics which I knew I would not dare to do myself, and felt a vicarious sense of achievement when she performed them. Her name became the centre of many fights and struggles.

I grew up out of her memory. (24)

In the poem ‘Elegy on the Heroine of Childhood’, composed after Vernon read about White’s death on the eve of the Second World War, the silent Hollywood star is not simply a dead movie icon. Her memory is the memory of childhood itself, evoking the early days of the First World War (“the time when Arras fell”) and the childhood locations of the Uplands (“From school’s spiked railings, glass-topped, cat-walked walls…We run to join the queue’s coiled peel”). Her pale image, resplendent and flickering on the cinema screen, becomes the ghost that haunts Vernon’s mature imagination:

Week back to week I tread with nightmare speed,

Find the small entrance to large days,

Charging the chocolates from the trays,

Where, trailing or climbing the railing, we mobbed the dark

Of Pandemonium near Cwmdonkin Park.Children return to mourn you. I retrace

Their steps to childhood’s jealousies, a place

Of urchin hatred, shaken fists;

I drink the poison of the mists

To see you, a clear ghost before true day,

A girl, through wrestling clothes, caps flung in play. (25)

Her image is entwined completely with the physical recollections of childhood (“episodes and half episodes…photographed”) and her multiplying death scenes become a cheap way to cheat death: her resurrection and immolation in each new movie becomes a symbol of cycles, renewal and therefore permanence. Pearl White defeated time until she actually died in real life and this immaculate image was brought back to reality and childhood ended:

How near, how far, how very faintly comes

Your tempest through a tambourine of crumbs,

Whose eye by darkness sanctified,

Is brilliant with my boyhood’s slide.

How silently at last the reel runs back

Through your hundred deaths, now Death wears black.

While it is true that Swansea was a positive place for Vernon — after all, along with the Gower, it was the place that healed him and gave him back his life — in these poems it is usually defined by loss and grief: the elegies to Dylan, his childhood and Pearl White, and the town demolished in the Blitz. The fact that they record the things that have been lost in the end serves to preserve them. For Vernon, this process is fundamental to his understanding of life, death and art.

If Vernon could mythologise Swansea in this way it was because, for him, the town was already a symbolic place, a site tied into his own, extended, poetic universe. It was a tribute to the vitality and atmosphere of the place that it could sustain such pressure. How true this view was is not really the point. The “loitering marvel” that he painted was a place of the imagination, which made it immortal. It was a half-truth: at a certain moment Swansea had a creative vitality and depth that was unusual, not only for Wales. This meant everything to Vernon and partly gave him back the paradise he lost when he left Repton College: a circle of inspiration, comfort, camaraderie and love. For him, Swansea was like a town from the Italian Renaissance but without any patrons, and so he made high claims for it:

Swansea is a town where art is alive. If it became a cultural centre or a resort where art was fashionable and where it was always being discussed but never created, it would be a town where art was dead. Such a Swansea, such a Salzburg-on-the-Tawe I could not imagine; but a Swansea without art I cannot imagine either. There is no room in Swansea to be pompous without it being ludicrous. But the town itself, the town of windows between hills and sea, is unforgettable. What should Swansea become? It should, I think, generate its own species and become what it is now, a town where art is alive. If you give Swansea more power, make it the capital of Wales, then you spoil everything. I want Swansea to be, not the capital, but the interest of Wales. (26)

In the ‘Ode to Swansea’ he made this loyalty to his half-imagined utopia clear:

Prouder cities rise through the haze of time,

Yet, envious, all men have found is here.

Here is the loitering marvel

Feeding artists with all they know.

Swansea, a once great town of global significance, provided him with a symbol of creativity and the immortality of man.

III: Gower and Landscape

But what about Gower, “the first of places for him,” in the words of his widow, Gwen (27)?

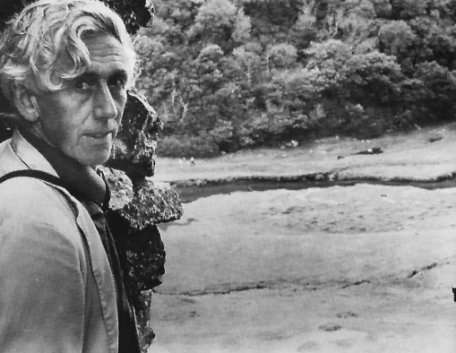

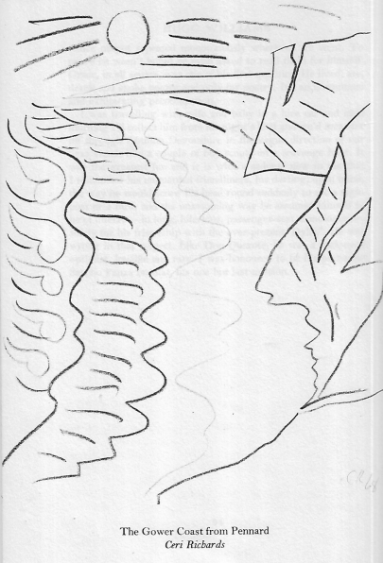

His friend, the poet Michael Hamburger, wrote that “the Gower landscape is as inseparable from my recollections of Vernon as his poetry and person are inseparable from the place in which he chose to spend all his mature years” (28). His sometime neighbour, the Swansea painter Ceri Richards, described the experience of being given a tour of Vernon’s “immediate and familiar” Gower:

He took you straight to his personal vantage points. He was remarkably sure-footed. Far down on the foreshore, when you called to see him, and the tide was right — you saw him from aloft — and he was master with the prawns, crabs and lobsters, striding through pools, over rocks slippery with seaweed, up rocky faces and sand dunes, and through acres of bracken and gorse, in his own natural diversity of ways. (29)

This was the south coast of the peninsula, the golden belt of sandy bays, remote coves, prehistoric caves and limestone cliffs extending from Bracelet Bay sitting in the lap of Mumbles Lighthouse to the grand sweep of Rhossili and Worm’s Head (“end of Earth, and of Gower!” 30). Vernon once defined the geography that shaped the early imagination of Dylan Thomas as “the sea town, the park, and the Gower peninsula stretching from Mumbles to Rhossili, and from Rhossili to Worm’s Head,” (31) and this almost exactly demarcated his own interior landscape, too. Unlike Swansea or Germany or the Ireland of Yeats, South Gower was, for him, a self-enclosed world, a permanent and privileged micro-continent that supplied him with many of the tools he needed for his own work. He was a part of this landscape and was fully attuned to all aspects of its environment. He could read it closely and created a network of symbols out of its raw materials: the sea, geology, birdlife and vegetation; the storm beaches and sand dunes; the seasonal winds and the changing light.

The first true success of Vernon’s second period of poetry (that is, the period of poetry he was content to see published, rather than incinerated) was ‘Griefs of the Sea’, an elegy to dead sailors that he “heard” one day “coming out of the grasses of the cliffs of Pennard and Hunt’s Bay” (32). Gwen Watkins recalled that

the spring and autumn equinoxes were times of great fascination for Vernon; the gales then came more exactly to the dates than they seem to now, and the idea of day and night standing equal as the storm-winds raged round his home was immensely exciting. (33)

In this poem the wild Gower winds are the driving element of natural chaos that once claimed the lives of the sailors that the poem mourns: “a horrible sound”, “a wicked sound…that follows us like a scenting hound”, the sound of death and therefore time. Some of the symbols are established here that would recur in the rest of his work: the “blind” waves and their “wild wreath of foam” and “weeds…beneath the sea”; the wild wind and the ominous stars (34). This is the beginning of a private network of imagery that would become more elaborate and complex over time; the poem lacks the taxonomy of colour and the precise inventory of Gower’s wildlife that would become central to his work, but it is the first example of the Gower being used by Watkins in the way it would always be from then on. The landscape inspires “thought” which, in turn, “changes” or transfigures it: a walk on a windy day to his favourite bay sparks a vivid meditation on death, mourning and memory. Random natural elements are transformed by a cosmic drama that is, ultimately, the same thing as his own human drama. As he would later put it, “a place is altered by a poem” (35).

One of the most important places in Vernon’s elect landscape was Pwlldu Bay at the mouth of Bishopston Valley, a recurrent location with its own natural and symbolic properties. In ‘The Return of Spring’, the stream that winds through the valley down to the beach is a fresh course of water in which “all secrets under the Earth grow articulate” (36). These are the secrets of time: at the bottom of the valley, beyond the great shingle bank that separates the beach from the wood, the stream and the reed beds, “the eyes turn seaward/To laugh with waves that outlive us”; “the receding seawaves…knock at the hour-glass,” a majestic and immortal rhythm that finds its cyclical residue in the sand, pebbles and rocks that construct the landscape of the bay. Meanwhile, in the valley, leaves mend “Winter’s wild net”, “taut branches exude gold wax of the breaking buds”, “sweet finches sing” and “diamonds of light” suffuse the woodland as life returns to “bring beauty to Earth.” But with the annual regeneration of nature there is also darkness, decay and death: as Roland Mathias recognised, “an awareness of the necessary interlocking of light and dark, of death and life” was a central tension, or balance, in Vernon’s work. For Mathias, “grief and darkness” lay at the heart of Vernon’s Christianity and his conception of life itself: “it was through grief and darkness, not through the near-whites of nature or human satisfaction, that he had perceived the single, yet multiple, pattern of Christ” (37). This is what he saw at Pwlldu, with spring light breaking through Bishopston Valley (“I divine those meanings/Listening to tongues that are silent”): the secret patterns of natural regeneration, cycles of life always touched by death. This was the balance that he found in Plotinus and the New Testament that provided him with some measure of understanding to replace dread: “What first I feared as a rite I love as a sacrament”.

At Pwlldu, the “waves…outlive us” and Bishopston stream is witness to the regeneration of life within the cycle of seasons. The beach and valley are sites of eternity, an idea revisited in ‘Ballad of the Equinox’ which emphatically declares Pwlldu “an eternal place!” Again, the landscape is a stage on which this cosmic human drama is played out:

There the great shingle-bank

Props a theatrical scene

Where guess the generous dead

What lovers’ words may mean. (38)

In ‘The Return of Spring’, Watkins writes: “Thunder compels no man, yet a thought compels him.” The natural world has no meaning, symbolic or otherwise, without the “thought” that makes meaning. It is the human faculty to divine the patterns of nature — or in the poet’s own theological system, the patterns of God — that recreates the landscape and makes it intelligible in artistic and philosophical terms (“a place is altered by a poem”). In ‘Ballad of the Equinox’ this process is at work, and explicitly so: for Watkins, the world’s a stage, but man is no mere player: he makes meaning.

In ‘Return of the Spring’, Bishopston stream carries light and life in its cool and fast flowing water; in ‘Ballad of the Equinox’, this same water flows into the pool at the foot of the shingle bank, under the stones and into the sea. “The black stream under the stones/Carries the bones of the dead,” Vernon writes, transforming Pwlldu into a dark memorial, a “sterile porch of Hell” with “the devil…in the wild winds” and “the tides of the grave” dispensing in its foam “A spent and weary log/A crab with a million eyes/And a cast-up, wicked dog”. In a later poem, ‘Bishopston Stream’, the water is still “black” but once again functions as a symbol of renewal, balance and life: “Out of the wood I come, astonished to find you/Younger and swifter” (39). The stream is loaded with dual meaning in this poem, as the water speaks with two voices: a meeting place and an image of separation. The duality, the balance, the tensions between light and dark, white and black (black water, white stars, white foam) hold the key to Vernon’s method and thought. Opposites are never reconciled and so nothing is resolved in this way. Opposites exist within each other without losing their separate qualities. The lack of resolution is the resolution. The poet’s only answer to the problem, or the tragedy, of time is to learn how to interpret it: “Even by day you run through a continual darkness/Could we interpret time, we should be like the angels”.

Pwlldu, Hunt’s Bay, Rhossili, Oxwich, Three Cliffs, Paviland Cave, Worm’s Head, Crawley Wood: these are the Gower landmarks that populate Vernon’s poetry and are transformed by it. They have the same tangential relationship to memory and lived experience in the poems as Swansea does. As Gwen Watkins remembered it, the poem ‘Rhossili’ was partly inspired by “a disastrous canoe trip which Vernon made at the beginning of the war” with his friend David Lewis:

They intended to arrive on Rhossili beach and camp for a night or two; but their failure to practise double-paddling or to check the times of the tides, or to load their gear evenly, led to their arrival very late at night. They were instantly apprehended by the local Home Guard as German airmen coming ashore. Their English public-school accents did not help matters, but after hours of questioning, they were allowed to camp for the rest of the night. David Lewis went home by the first bus the following morning, but Vernon stayed on, and went out to the end of the Worm. (40)

This mildly calamitous expedition is reimagined as an epic Homeric voyage: Worm’s Head becomes “The rock of Tiresias’ eyes!” and Vernon a latter-day Odysseus, battling through the currents from Pobbles to “the needle around which the wide world spins,” about twelve miles west. He climbs the face of the worm and is attacked by screaming herring gulls who lunge at his head, “crazy with fear for the loss/of their locked, unawakened young”; later, lying on the sands at Llangennith, he watches “dolphins, plunging from death into birth” that are “held by the Sybil’s trance!”

Rhossili figures quite precisely in this account and anyone familiar with the terrain would be able to recognise the wreck of the Helvetia or the blow hole near the centre of the Worm. But these physical landmarks are filtered through the transformative properties of memory which, in this case, finds expression in the mock heroic narrative. Like ‘Elegy to a Heroine from Childhood’, ‘Rhossili’ is a particular type of memory poem that does not try to precisely recall the past, but attempts to convey the way memory works in the imagination, combining recollection with sensation and experience. ‘Rhossili’ was not written for the sake of describing Rhossili: it was not about the place. The origin and content of the poem remain oblique without Gwen’s account of Vernon’s canoe trip or some familiarity with the physical and natural features of landscape and geography. The poem exists to question the nature of memory on a personal scale and within the wider context of human perception and creativity.

The presence of Gower in the poetry of Vernon Watkins is not just evident in, say, poems named after beaches. Kathleen Raine was correct when she noted that all of Vernon’s poems “seem…like parts of a single poem” (41) and Roland Mathias made a similar point when he wrote that “the truth he was after had been caught, if at all, only in an endlessly mended net of words and symbols” (42). The natural imagery of the peninsular is woven densely into these poems and across the whole body of his work. But however precise, evocative or vivid these details were, he was not writing about the landscape of the Gower for its own sake. He was not a landscape poet. He never intended to be merely descriptive, a point he made explicit to George Thomas in 1967: “I’m fundamentally a religious and metaphysical poet. I’m not a nature poet or a descriptive poet” (43). And, in a talk delivered in 1961 (‘Poetry and Experience’), he explained:

Constancy within change is the theme of so many of my poems, and until it enters a poem I can never find my imagination wholly engaged. I marvel at the beauty of landscape, but I never think of it as a theme for poetry until I read metaphysical symbols behind what I see. (44)

By all accounts the Gower was the most important place on earth for him but it had a strictly demarcated role in his poetry. It served a function, however rich and complex that function was. The Gower was one stage for his own human drama which, for him, was the human drama: to escape the domination of time and transcend the final fact of death. Even if it was the most important stage he had, it was still a stage: he was never really writing about Gower because he was writing about his own conflicts and concerns. As Mathias put it, Gower epitomised the entire world for Vernon Watkins and what he found here was not simply the pleasures and interests of the landscape itself or his own personal memories, but the ultimate revelation of truth and order.

IV: Nationalism and Poetry

In this sense, then, Vernon barely wrote about Wales at all. He loved Wales, but he had no intention of tying his work to the earth. Poetry, for Vernon Watkins, was an existential art, a private, even hermetic, affair. It was not meant to proselytise for a cause, however noble or historic that cause may be. And, importantly, Vernon did not consider Welsh nationalism to be a noble cause.

This was the one point of contention between Vernon and Yeats in 1938. Again, it was partly written down in ‘Yeats in Dublin’:

We talked of national movements.

He pondered the chance

Of Welshmen reviving

The fire of song and dance,

Driving a lifeless hymnal

From that inheritance.I thought of rough mountains,

The poverty of the heath.

‘Though leaders sway the crowd’, I said,

‘Power is underneath.

The sword of Taliesin

Would never fit a sheath.

In the same year, Keidrych Rhys tried to recruit Vernon to his new Welsh poetry movement with the taunt: “Did you know Yeats believes in National Poetry?’ He should have known this wouldn’t work. At their meeting, Yeats asked Vernon about the state of Welsh poetry and told him, “Poetry must not be nationalist, but must be national” (45). Vernon responded: “How can there be a national poetry?” The idea was inconceivable, a tragic limitation on the imagination. Taliesin himself could not be reduced to the national question; apart from anything else, the working bard was employed by rival and sometimes warring princes and was therefore as much a symbol of national disunity. In fact, nationalism was the one thing that had, in Vernon’s eyes, blighted some of Yeats’s own work, which was otherwise beyond criticism.

Despite the hairsplitting (‘national’ rather than ‘nationalist’), Vernon recognised Yeats as the “great nationalist” that he was and therefore, in this regard, considered him subject to an “arrogant blindness” (46). He was responding here to a political disposition later defined by Conor Cruise O’Brien as a volatile mix of Anglophobe Irish nationalism and aristocratic authoritarianism that contained within it a “sometimes mildly critical…never hostile, almost always respectful, often admiring” attitude towards fascism (47). In contrast, Vernon, though politically naive in many ways, detested fascism and Nazism on first contact. He had been on holiday in Germany with his sister Dorothy during the Nazi book-burnings and almost caused a diplomatic incident, as Gwen Watkins recalled:

Vernon told me that two German friends had taken him to a Nazi gathering…and they discovered Nazi officers lighting a bonfire and people were bringing books and laughing and cheering. The Nazis shouted out the names of the authors as they threw the books. The friends wanted to leave, but Vernon heard the name of Heine shouted out, and began to try to push to the front to save the books. The two friends rapidly took his arms and rushed him away in spite of his struggles. He would say jokingly that if the officers had caught him I would probably have had to find someone else to marry. (48)

This was a visceral response to the violent philistinism of the Nazis; Vernon would also recoil from the totalitarian racial utopia that they planned, a vision that was anathema to his own personal and universalist creed. As Nazi and fascist power grew in Europe his instincts diverged from Yeats, who became more excited and enthusiastic with each victory. Writing to a friend on the day Chamberlain flew to Munich, Vernon used unusually vulgar terms: “Don’t you think that all racial purists ought to be pissed on hard and long — or isn’t that too good for them?” (49). In the end, it was his fluent German that would enable him to fully contribute to the anti-Nazi cause when he was recruited to Bletchley Park in 1941.

As Gwen later wrote, Vernon “saw no meaning in narrow nationalism” of which Nazism was one particularly virulent manifestation, but which he would also reject in the more benign form of a proposed Welsh poetry movement. When he was invited to join the ‘national’ poets of the ‘New Wales Society’ in 1939 (of all times!) his response was scathing: “those nationalists who are most bitter at this moment should try to distinguish between the imperfections of their country and the imperfection of their style” (50). They would, in effect if not intention, be making the same errors as Auden and Yeats, but without the talent to back it up and built on a brittle foundation of parochial resentments and historic grievance. He held nothing but contempt for this position and was more than happy to make common cause on this point with Dylan: “We were both Welsh, both Christian poets, we both preferred the sea to politics and hated nationalism” (51). As Vernon’s biographer Richard Ramsbotham noted: “what was important for Watkins about Yeats had nothing to do with nationalism or political causes, but with the universal character of his individual imagination” (52). Universality was the only legitimate aim for poetry; the imagination its only cause.

The whole objective of Vernon’s life as a poet was to escape the limits of time. Memory and the act of eulogy were key components to this, but he did not intend to use them to put new or different limitations on the imagination. As Raymond Garlick noted, there is a strain of Anglo-Welsh literature in which “the past is a constant theme, triumphant and golden”, a consciousness of belonging to “a country of great age,” as R. S. Thomas put it (53). This was a tendency that would attempt to find its voice in the New Wales Society and really would find a voice in R. S. Thomas’s own work. This was not a concern for Vernon Watkins. Even when he invoked Taliesin, the historical associations were slight and the intention to revive “tradition” largely absent. His mature work was driven by his own revolt against time, in which all of the material that he had collected from his past and his present was put to use. Time reigned, but not the national timeline. The idea of a collective past, a national history or a Welsh tradition had no purchase on his true ambition. He was not a poet of Wales, writing to extol the landscape or glorify the past. For this reason, his refusal to fully exploit “Welsh heritage” or take it up as a cause was not only a necessity, but a source of strength. He consciously avoided all of the traps that caught Yeats. He had no interest at all in adopting the collective grievance fueled by the nationalist party. He refused to produce propaganda, however erudite it may have been.

Mathias recognised that there was no “revolt or reconciliation” (54) in this attitude, even if he did not fully approve of it. This was not a fight or an argument or a revolution, it was a matter of fact and fate; the result of private experience and personal philosophy. Vernon Watkins was a Welsh poet but he did not write for Wales and he did not belong to Wales. That was a good thing.

- Vernon Watkins, ‘Yeats in Dublin’ in The Collected Poems of Vernon Watkins (Golgonooza Press, 1986), p.65

- Christopher Isherwood, Lions and Shadows (Vintage, 2013), pps. 74-5

- ‘Insert for Spectrum’, interview with Dr. George Thomas, 16th February 1967 in Vernon Watkins on Dylan Thomas and Other Poets & Poetry, ed. Gwen Watkins and Jeff Towns (Parthian, 2015), p.128

- Vernon Watkins, ‘Poetry and Experience’ in Vernon Watkins on Dylan Thomas and Other Poets & Poetry, p.155

- Glyn Jones, ‘Whose Flight is Toil’ in Vernon Watkins 1906-1967, ed. Leslie Norris (Faber and Faber, 1970), p.25

- Quoted in Richard Ramsbotham, An Exact Mystery: The Poetic Life of Vernon Watkins (The Choir Press, 2020), p.187

- Roland Mathias, Vernon Watkins (University of Wales Press, 1970), p.11

- Quoted in Ramsbotham, p.6

- Gwen Watkins, ‘Vernon Watkins 1906-1967’ in Vernon Watkins 1906-1967, p.15

- Kathleen Raine, ‘The Poetry of Vernon Watkins’ in Vernon Watkins 1906-1967, p.38

- Ibid., p.41

- Roland Mathias, ‘Grief and the Circus Horse: A Study of the Mythic and Christian Themes in the Early Poetry of Vernon Watkins’ in A Ride Through the Woods: Essays in Anglo-Welsh Literature (Poetry Wales Press, 1985), p.120

- Mathias, Vernon Watkins, p.97

- Raine, p.38

- Mathias, Vernon Watkins, p.98

- Vernon Watkins, ‘Taliesin in Gower’, Collected Poems, p.184

- Watkins, ‘Taliesin in Pwlldu’, Collected Poems, p.353

- Watkins, ‘Taliesin and the Spring of Vision’, Collected Poems, p.224

- Dylan Thomas, ‘Return Journey’ in Dylan Thomas – The Broadcasts, ed. Ralph Maud (J.M.Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1991), p.183

- Watkins, ‘Ode to Swansea’, Collected Poems, p.285

- Watkins, ‘The Broken Sea’, Collected Poems, pp.80-1

- Watkins, ‘A True Picture Restored — Memories of Dylan Thomas’, Collected Poems, p.286

- Watkins, ‘The Place and the Poem’ in Vernon Watkins on Dylan Thomas and Other Poets & Poetry, p.176

- Ibid., p.178

- Watkins, ‘Elegy on the Heroine of Childhood’, Collected Poems, p.4

- Quoted in Gary Gregor, ‘Swansea’s Other Poet: Vernon Watkins’ in The Journal of the Gower Society, Volume 65, 2014, pps. 55-6

- Gwen Watkins, ‘Vernon Watkins 1906-1967’, p.16

- Michael Hamburger, ‘Vernon Watkins, a Memoir’ in Vernon Watkins 1906-1967, p.48

- Ceri Richards, ‘Remembering Vernon’ in Vernon Watkins 1906-1967, p.95

- Vernon Watkins, ‘Rhossili’, Collected Poems, p.119

- Watkins, ‘The Wales Dylan Thomas Knew’ in Vernon Watkins on Dylan Thomas and Other Poets & Poetry, p.111

- Quoted in Ramsbotham, p.85

- Gwen Watkins, ‘Taliesin in Gower: Vernon Watkins — A Retrospect’ in The Journal of the Gower Society, Volume 48, 1997, p.23

- Vernon Watkins, ‘Griefs of the Sea’, Collected Poems, p.7

- Watkins, ‘The Place and the Poem’, p.175

- Watkins, ‘The Return of Spring’, Collected Poems, p.116

- Mathias, ‘Grief and the Circus Horse’, p.111

- Vernon Watkins, ‘Ballad of the Equinox’, Collected Poems, p.189

- Watkins, ‘Bishopston Stream’, Collected Poems, p.315

- Gwen Watkins, ‘Taliesin in Gower’, p.25

- Raine, p.40

- Mathias, ‘Grief and the Circus Horse’, p.91

- Interview with George Thomas, p.129

- Vernon Watkins, ‘Poetry and Experience’ in Vernon Watkins on Dylan Thomas and Other Poets & Poetry, p.163

- Quoted in Ramsbotham, p.169

- Ibid., p.186

- Conor Cruise O’Brien, ‘Passion and Cunning: An Essay on the Politics of W. B. Yeats’ in Passion & Cunning: Essays on Nationalism, Terrorism and Revolution (Simon & Schuster, 1988), p.54

- Quoted in Ramsbotham, p.105

- Ibid, p.176

- Ibid., p.186

- Ibid., p.127

- Ibid., p.186

- Raymond Garlick, Introduction to Anglo-Welsh Literature (University of Wales Press, 1972), p.53

- Roland Mathias, Anglo-Welsh Literature: An Illustrated History (Poetry of Wales Press, 1986), p.94